About Hindu Sacred Music

The origins of Indian classical music can be traced to the Vedas, the oldest scriptures in the Hindu tradition. The genre is also closely associated with and influenced by Indian folk music and Persian traditions. In general, it is based on ragas and tala (rhythmic beat patterns) played on the Veena (or Been), Sarangi Venu (flute), Mridanga(or Tabla) (traditional Indian instruments). The Sikh Scripture, for example, contains 31 ragas and 17 talas which form the basis for kirtan music compositions. (This link describes the relationship between Hinduism and Sikhism.)

There are 72 seven-toned scales in Indian music, hundreds of fewer-toned scales, thousands of melodic ‘moulds’ and 35 time signatures.

Hindustani music predominates in Northern India and seems to have its origins around 1000BC, and further developed between the 13th and 14th centuries AD with Persian influences and from existing religious and folk music. It is divided into two main forms, Khyal and Dhrupad, along with several other classical and semi-classical forms. The Persian influence is perhaps most obvious in the instruments, style of presentation, and ragas. Also, as is the case with Carnatic music (more common in southern India), Hindustani music has assimilated folk tunes; ragas such as poetic Kafi and Jaijaiwanti are based on folk tunes. Both traditions claim Vedic roots, and history indicates that they diverged from a common musical stem around the time of the 13th century.

Hymns (or Samaveda) are traditionally sung by Udgatar priests in a chanting style.

Carnatic music appears to have emerged in the 15th and 16th centuries. It tends to be more rhythmically intensive and structured than Hindustani music and has more in common with the Western classical genre. Carnatic ragas are generally much faster in tempo and shorter than their equivalents in Hindustani music, and accompanists have a much larger role to play.

The meaning of the original Sanskrit word Carnatic is “Soothing to the ears”.

There are also notated lyrical poems that are performed possibly with embellishments and interpretations according to the performer’s ideology.

The 15th Century composer Purandara Dasa is credited with having founded today’s Carnatic Music. He systematized its teaching methodology by devising a series of graded lessons such as swaravalis, janta swaras, and kritis, that are followed by teachers and students of Carnatic music to this day. He introduced the Mayamalavagowla as the basic scale for music tuition. Another important contribution of his was the fusion of bhava with raga and laya in composing.

Purandara Dasa was the first composer who started commenting on the daily life of the people as well as worship in compositions. He introduced the usage of popular folk language and helped bring folk ragas into the mainstream.

Instruments common to Carnatic music include the venu (flute), gottuvadyam (a 21-stringed, fretless lute), harmonium, veena; percussive instruments like the mridangam, kanjira, ghatam; and the violin.

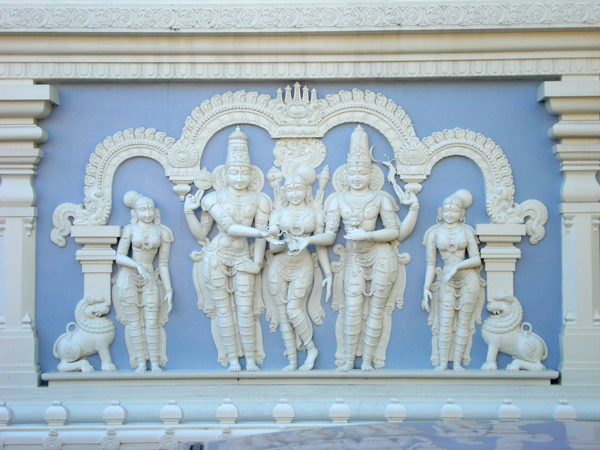

The Bauls of Bengal are an order of musicians dating back to the 17th century, who play a form of Vaishnava music (Vaishnavism being a branch of Hinduism focused on the veneration of Vishnu) using a khamak, ektara and dotara (resonating stringed instruments). The word Baul comes from Sanskrit batul meaning divinely inspired insanity. They are a group of mystic minstrels influenced by Sufism and Buddhism. They are wandering singer-poets whose earthiness reflects on matters such as work and love. They have also been influenced by Hindu tantric sect of the Kartabhajas and also by Sufi sects. Bauls travel in search of an internal ideal, called Maner Manush (Man of the Heart).

There is much common ground in Muslim, Hindu, and Sikh devotional songs. They all speak of an ultimate reality and a search for spiritual guidance. Instrumentation and language may differ, but the essence is the same.

Another aspect of interest to religious aficionados is that some of the leading poets and singers of India and Pakistan have written devotional poetry and have sung devotional songs outside their religious traditions.

It is believed by some that music in India is of divine origin and that the gods gifted it to man for his enlightenment. It’s indicative of the renaissance Indian music has enjoyed in recent years that it is no longer considered ‘degrading’ to be a musician.