Zoroastrian Sacred Music

Zoroastrianism in Persia all but disappeared as a result of the Muslim invasion in 637 C.E. Small, disparate pockets of the faithful only survive in some remote Iranian villages, while over the centuries many fled to India in order to enjoy greater religious freedom. Though Zoroastrians represent a tiny community in the world today, it maintains significance for several reasons, not least of which is the generally-held opinion that it is the world’s first faith to profess monotheism.

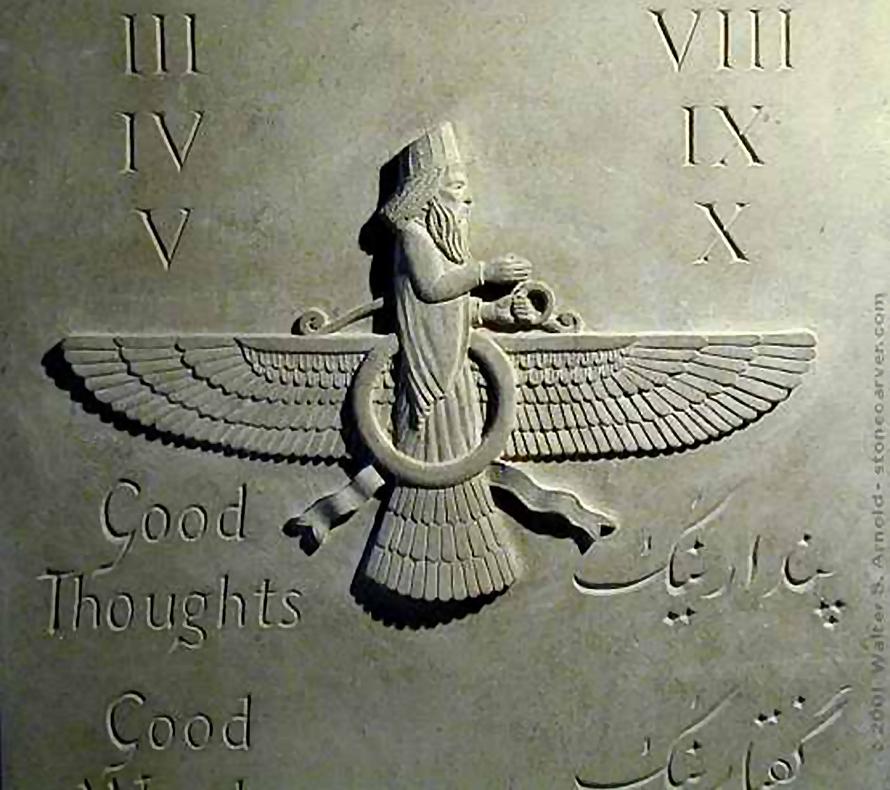

The core ideas of the Zoroastrian faith are presented in The Gathas, 17 songs composed by the prophet Zarathushtra approximately 3700 years ago in Iran, after having a vision in which the deity Ahura Mazda imparted his holy teachings. The Gathas consist of 241 stanzas, of poetry containing Zarathushtra’s prophecies. The mechanic of committing these words to song is possibly an aide memoire in a period of history long before writing and drawing were established as ways to record events.

Based on the structure and rhythm of Zoroastrian texts, Zoroastrian Sacred Music and musical performance is considered a very important chore by Zoroastrians. The complexity of rhythm involved in the playing of Zoroastrian melodies, has meant that many Zoroastrian songs have become obsolete and forgotten. Also, further interruptions in the musical tradition have come about as a result of several Islamic incursions into territories where Zoroastrianism was the primary religion. One can still hear Zoroastrian sacred songs in holy buildings such as Darbe Mehr, or sun worship temples.

One can still witness the live performance of gathas by certain Mubids, as well as readings of the Avesta. But the lack of continuity that would have been a product of maintained clerical vocation means a lot of the canon has been forgotten or is performed in an intentionally unmusical or discordant style. The oral tradition of much Zoroastrian Sacred Music historically used in Zoroastrian ceremonies has been lost, such as the ‘Ferdog’ musical songs in graveyards.

In Zoroastrian fire temples, bells are frequently used to augment singing. The bells are tolled at certain and fixed intervals during ceremonies. According to some records, the Zoroastrian religious music has influenced some Christian ‘tartils’ (recitations) during the dawn of Christianity. The meter of Zoroastrian Sacred Music is very natural, lyrical and harmonic. The cadence of the music can be heard as very natural, flowing, and to a large extent chiming with speech patterns.

Some Zoroastrian musical pieces are comparable to the tambourine music used in ancient Iran presently chanted in Kermanshah or certain Islamic/prayer melodies such as the Naderi method of recitation of the Quran and some of the pilgrimage songs and prayers. As we are aware the Gregorian songs originated from the East and these songs and melodies are greatly influenced by Hebrew melodies that are in use in Israel and Syria as well as regions where traditional Greek and Byzantine music is heard.

Some Zoroastrian musical pieces are comparable to the tambourine music used in ancient Iran presently chanted in Kermanshah or certain Islamic/prayer melodies such as the Naderi method of recitation of the Quran and some of the pilgrimage songs and prayers. As we are aware the Gregorian songs originated from the East and these songs and melodies are greatly influenced by Hebrew melodies that are in use in Israel and Syria as well as regions where traditional Greek and Byzantine music is heard.

A large part of the Zoroastrian community resides in India and Iran. There are just an estimated 200,000 Zoroastrians left worldwide, and their population continues to decline steadily. It is commonplace in the Zoroastrian community that they tend to marry late and often do not bear children. These are among the main reasons behind the community’s declining numbers. Additionally, as Zoroastrianism does not accept children of mixed marriage and inter-religious marriages, newcomers into their faith via means other than birth are rare.

The Zoroastrians living in India are referred to Parsis. They are prominent in many areas of Indian society. Some influential and notable Parsis include J.R.D Tata, the business tycoon and a noteworthy philanthropist; Pherozshah Mehta and Dadabhai Naoroji, two historically well-documented early freedom fighters in India against the imperialist powers; Music Director for Life of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Zubin Mehta; Freddie Mercury (born Frederick Bulsara) late vocalist and writer for the band ‘Queen’; and the popular and award-winning novelist, Rohinton Mistry.